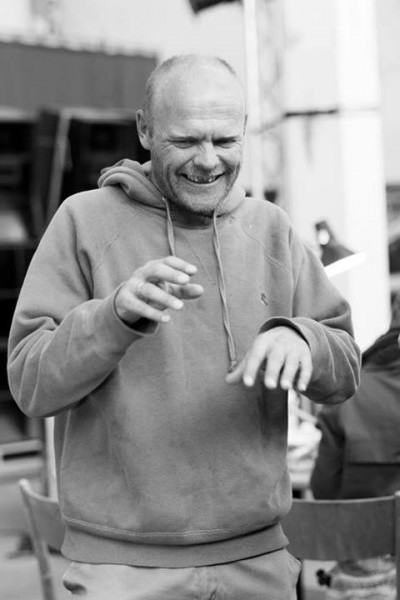

I was recently asked some questions by Alparslan Teke of the Middle East Technical University in Ankara, Turkey about my instrument building practice, and I thought I might share the answers here.

1. How did you start making or altering electronic musical devices?

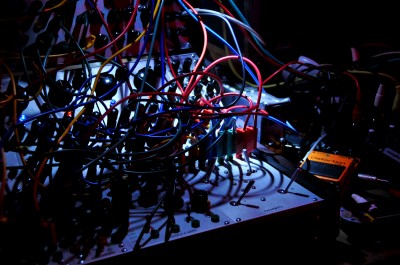

To make a long story incredibly short: I have always been interested in sound. However I lacked the discipline as a teenager to learn how to move my fingers quickly up and down the neck of a guitar or the keyboard of a piano. In my confusion, I considered “making sound” to be the same as “making music”. When I later figured out that most sound around us is in fact un-pitched, un-tempo-ed and therefore non-musical, my world opened up. But I discovered that most devices for making electronic sound still assumed one wanted to make “music” with them, so I started to take them apart to remove the “musical” part of the interface, or simply create my own from scratch, first in the Pure Data programming language and later with analog electronics.

2. In which relevant fields were you educated?

None. I studied literature in my bachelor’s studies, and silversmithing before that. Perhaps that accounts for my obsession with objects with tiny parts? Other than that I am not only entirely self-educated, but also in all my school years I nearly failed every math class which was ever forced on me. The fact that I am internationally recognized as a builder of electronics and a programmer of computers remains a gigantic mystery to me.

3. What were your motivations and/or purposes when you started, and (how) did they transform?

My instrument-building reflects an economic reality one faces as a non-academic, non-institutional artist these days. There is so much digital sound out there right now, and no one pays you for making any of it. But since we are working in the era of the “pro-sumer”, there are plenty of people who are constantly spending money on the tools to make their own sound. So what started as a way of taking control of my own tools and wrestling them away from the traditional music world ends up being an economic relationship with the music world all over again once they start to take interest in my way of working.

4. Do you consider this artistry (of making electronic/electroacoustic musical instruments) as your profession? If not, do you have any else?

I have no plan B at the moment. This is my day, night, weekday, weekend, summer, and winter job.

5. What words or concepts would you use to describe things you’ve created?

Non-linear, chaotic, generative, intuitive, iterative, multi-modal, phenomenological.

6. What related activities do you do that are directly or indirectly related to this occupation? (such as using the devices you made in performances, conducting workshops, etc.)

Currently a third of my time in this field is spent making instruments for sale. Another third is spent preparing for, traveling to and playing gigs. The last third is spent teaching.

7. Where and how do you get your ideas that end up with different devices?

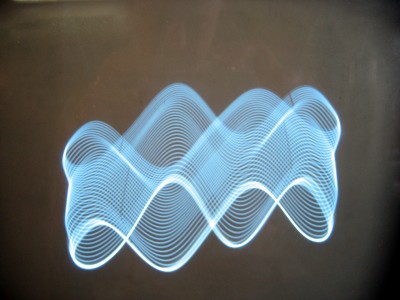

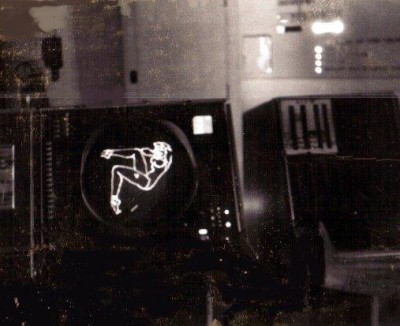

Up to quite recently, almost everything in the analog synthesizer world was some kind of riff on something which was made in the 1960’s and 70’s already. This happens due to an unprecedented access to information about those devices which was much more mystical and unreachable at the time they were made. Despite the efforts of their inventors to share the knowledge at the time in many cases, the widest propagation effect was delayed until internet access became largely ubiquitous. I still think some of the best work in the field was done back then, and I spend a lot of time looking at old designs of audio and video devices from many eras, as well as related readings on the cultural, aesthetic, and philosophical ideas of the time which gave birth to these machines. Some of my favorite eras are the 1930’s (optical synthesis technology), the 1950’s (early analog and digital computer vector graphics), the late 1960’s (patchable, cybernetic analog computers become Buchla synthesizers), and the early 1970’s (after the Sony Portapak, television comes unglued through the work of Dan Sandin, Steve Rutt, Bill Etra, Steina and Woody Vasulka, Nam June Paik and others). However, the latest developments of hybrid digital/analog synthesizers have given me great hope and faith that finally we can also move on from these older models, and stop imitating drum machines from the early 80’s for the next 40 years.

8. Where and how do you get your raw material or components?

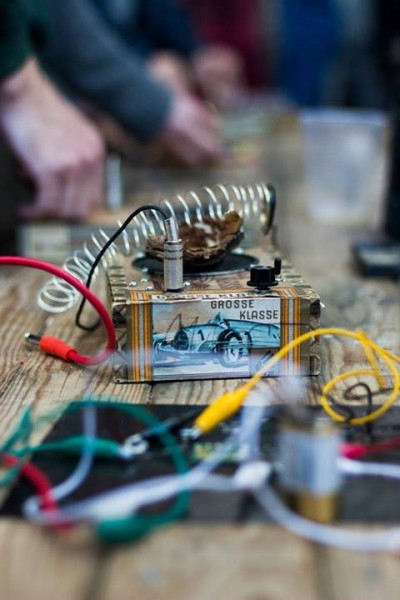

Small local shops when I’m in a hurry, larger European suppliers when I’m not. I haven’t moved to ordering from China in bulk yet. Most of my wooden instrument enclosures come from flea markets, antiques shops, strange collectors I have met over the years, and EBay.

9. How much time of a day or week (or a month, a year) do you spend on the workbench? Do you have a working schedule?

Sometimes I sleep. Then I feel guilty. I don’t know how to take vacations since beaches bore me to death, so I always end up finding some way to make a project out of a trip.

10. What time of this is actually building something, and in which other ways you spend time there? Would you confine your occupation of creating new musical devices to only the activities you do on the workbench?

As I said, I am pretty much always working. If I am not building, performing, or teaching, you can usually find me in “my office” (currently a rather relaxed cafe-bar in the Kallio district of Helsinki) doing research.

11. Do you have a separate workshop to maintain your effort, or is it embedded in the place you live in?

I had a working space in my Berlin flat for several years. It was the most unhealthy thing I ever did to myself, and my quality of life improved dramatically when I started renting out a studio. In Helsinki, I share a small space with a couple other artists who are pretty much never there, but I do dream about getting a larger space for myself again once finances allow it.

12. Do you produce in large quantities? Do you use the devices you`ve made, or do you sell them? Does this occupation provide you a livelihood?

I make everything in very small batches. This is because I am too stubborn to get into modern, automated processes and compulsively do things in very difficult ways, by hand. There is such a giant market for Euro-rack synthesizers made in far more efficient ways, I feel like if I get involved in that it will be a race to the bottom in terms of cost and quality. Probably I’m just a huge control freak.

I stand by everything I have built, and I use my own instruments every time I perform. In fact, I can’t really stand using things other people have built unless it’s something that would be really redundant to make myself, like a 16 channel audio mixer.

I have been lucky enough to be able to live from my art for the better part of two decades now, but that has also meant that I must constantly re-evaluate what “my art” means. This is how commercial instrument building and teaching became folded into my work. As I said, there is no plan B. It’s too late in life for me to get a start in the banking industry.

13. With whom do you most frequently interact as part of this

occupation of yours?

Workshop participants. I have offered my workshops in artist-run spaces, in music and media arts festivals, and in bachelors and masters level university programs in a variety of areas, including but not limited to architecture, theater, visual arts, media studies, audiovisual design, and music conservatory studies, in countries across Europe, North and South America, and New Zealand. The participants of these workshops have come from all walks of life, from professional Scandinavian artists to Native American high schoolers who have been tragically mis-labeled as “problem students”. The oldest participant in one of my workshops has been nearly 80, and the youngest just 8. One of the most unique participants was completely visually-impaired, yet insisted he would solder together his own electronic instrument. With a bit of assistance, he did just fine.