Introduction

Over four days at the start of September 2010, I took a small tour with the intention of visiting various socially-excluded groups in Hungary. This tour was organized by András Nun in the context of the upcoming UH Festival in Budapest, and I was joined by Luka Ivanovic (Lukatoyboy, Beograd), Balázs Pándi (drummer for Merzbow, Kilimanjaro Dark Jazz, Venetian Snares and others, Budapest) and Péter Szabó (Jackie Triste, Budapest), as well as by our translator Julcsi Palkovics and two photo/video journalists from Index.hu, András Hajdu and Kálmán ‘Mao’ Mátyás.

Each location visited related to András’ work with human interest NGOs, and he described the theme of our excursions as “Poverty and Exclusion in Hungary–or–What Can an International Festival Representing Peripheral Music Do About the Problem of People Forced to the Periphery, How Can It Act Against Their Exclusion?”

On Social Art I

I rarely hesitate in giving my opinion about the majority of “political” or “social” art projects I see at festivals and museums. Those that know me have often heard my joke about the Dutch media artist who reads the words “Problems of Muslim Integration” on the front page of the Volkskrant and “New Developments in GPS” on the technology page and–EUREKA!–runs off to win the Golden Nica at Ars Electronica.

The formula is simple: apply consumer gadget A to social problem B and it’s culture to absolve the middle-class guilt of the iEverything crowd, with kickbacks to Apple, Sony and Microsoft. In this European subsidized arts ecology, I have seen too many artists and institutions pay lip service to whatever the social-ill-of-the-day might be as a way of expanding their financial (and thus technological) resources from a different funding pool. And since the cultural money pools dry up quickest in times of crisis, I expect this kind of thing happens more often now than ever before.

However, while I cannot speak to the UH Festival’s organizational interests in having a theme like “Go Social!”, I can certainly point out András Nun’s deep personal interest in trying to combine the two very different worlds he lives and works in daily. So it was on those grounds that I agreed to take part.

Monor & Budapest

Besides the incredible range of groups we spoke to–in one moment we stood talking outside the run-down, windowless houses of dirt-poor Roma in the town of Monor, and in the next we jammed with young, hip Budapest 20-somethings at a walk-in drug treatment center–was the bewildering array of institutional approaches to these groups. One homeless advocate in Budapest insisted with all his naïve, youthful Marxist ideology that the solution to their problem was simply “housing, housing and more housing”. Likewise, the director of a homeless day center only focused on the necessities of food and clean clothing, without taking any interest in the individual psychic conditions which might keep people in those circumstances.

Faced with approaches such as these, the artist has little room to intervene. The artist’s work has nothing to do with policy, or even advocacy, but rather with the honest communication of human experience between one person and another. And this is an area unapproachable by those who reduce living people to demographics.

Esztergom, Vanyarc & Told

So I was much more at home in the locations where art had already found its place–places like Esztergom, Vanyarc or Told, where young people from poor Roma or Hungarian families could find the space and materials necessary for creative expression through painting, music or dance. It was a strange artistic match, however, for Luka, Péter and I to find a common ground with them.

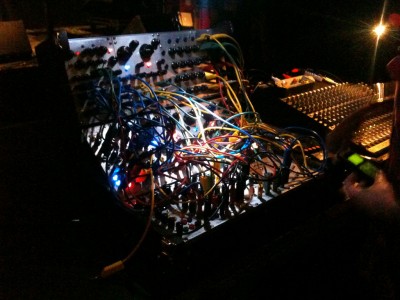

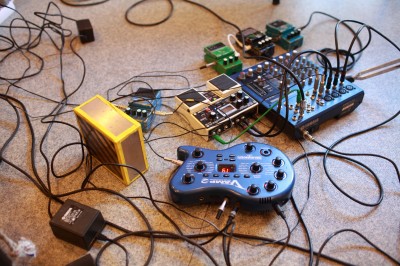

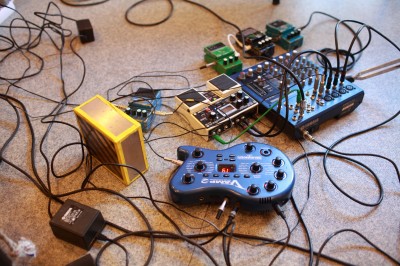

We showed up delirious from many hours on twisting Hungarian roads at each place with loads of noisy electronic boxes, not knowing what sort of response to expect. In Vanyarc, the kids quickly lost interest in electronics and instead presented us with a program of Christian song and dance in the Gypsy style. In Told, on the other hand, the situation was beyond chaotic. Luka and I quickly agreed that we would have the children draw pictures of sounds from their village life and sing–or scream, as it happened–them for us as a conducted choir rather than try anything with his noise-toys.

On Social Art II

Early on in the discussion of this trip, I brought up some of my concerns about the typical media artist approach to social problems. They came in response to a project proposal which would see a homeless man carrying around a brand-new digital recorder, and these recordings sampled during a live set at the festival. With a nod towards Cornelius Cardew’s Scratch Orchestra and The Great Learning projects, which brought amateur and untrained musicians together into a structured improvisational setting and reflected his preoccupations with a kind of “people’s art”, I wrote:

“I think if this will really work, some strategies of how the people/groups you have chosen to work with could represent themselves–without flashy gadgets costing half an average month’s salary and ‘professional’ mediation–would have to evolve. The very nature of that kind of experiment means that the results you get may not fit the sophisticated aesthetics of your festival audience in Budapest, however. An interesting paradox, and one which I think is necessary to allow to happen.”

This paradoxical jump between poor rural families and sophisticated city music scenesters inflicted what Luka called a “social jet lag” on the tour group after the four hour drive back from Told. As we boarded the A38 ship and went below deck to see the Peter Brötzman Trio play, our usual world of stages, bands and nightclubs turned upside down and suddenly became far more surreal than the rooms full of messy, loud Gypsy children we’d become somehow accustomed to.

Lessons in Junk

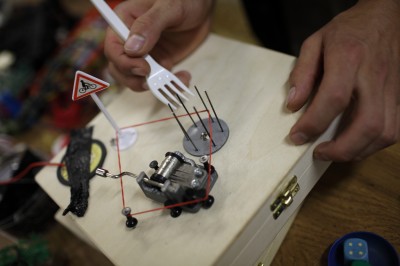

Speaking with Róbert Bereznyei (Tigrics, Budapest) in his synthesizer-stuffed studio apartment one evening, we found agreement on one point in particular: to go to poor people in the countryside and show them how to make art with expensive gadgets is like dangling the keys to the Ferrari in front of them and then driving off. Any meaningful artistic intervention or collaboration must involve things they might actually have access to once we leave, whether those things are built on the spot, commonly available or provided by some institution already there. Róbert put it quite simply.

“Teach them build things from junk,” he said.

This kind of alchemical approach suits me well, and before departing to Hungary I went through many workshop possibilities in my head. All of them required far more time than we had at our disposal. The average visit to any one of these places was about an hour and a half, when in fact we could have stayed one or many days getting a feel for the situation and developing proper connections with the locals. As it was, it felt like something between a rock-and-roll roadshow and a group of camera-toting Japanese tourists seeing the Statue of Liberty one day, the Grand Canyon the next and Sunset Boulevard the third.

Devecser & Bicske

With all this in mind, we set out to the town of Bicske on the last day of the tour to give a sound workshop for young Afghan refugees. Before this, however, we took a six hour detour to Devecser, where the local Roma community run one of the largest outdoor bazaars for West European trash I have ever seen in my travels through the East. Here we picked up a few kilos of Chinese plastic trinkets, springy metal bits-n-bobs and total-kaputt-elektromüll, and then happily went on our way. If there is one thing Berlin has taught me, it’s that a great workshop always begins with a trip to the flea market!

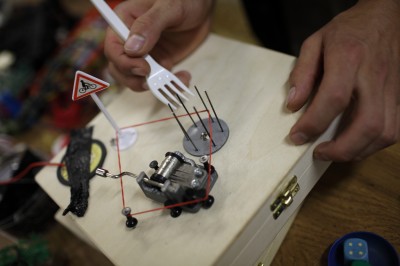

Each of the Afghan boys in Bicske had some horrible unspoken story to tell… of murdered family members, of being smuggled en masse in the back of a truck through Iran and Turkey, of sleeping rough in mountains and forests for nights without end and–at the end of everything–of the ordeals of the Hungarian legal system. I swallowed hard, hoping none of that would matter in the moment, dumped a load of junk on the table and showed them how to use a contact microphone to get life out of these dead objects.

By the end of the afternoon, several of the boys had constructed small wooden sound boxes and one, before leaving to Budapest for evening Ramadan services, even expressed a desire to learn something more about electronics. There aren’t too many moments in life when one feels like a superhero, but perhaps this was one of them…

Photography by András Hajdu and Péter Szabó. Thanks to the various organizations we visited and who hosted our workshops, including Az Utca Embere, A Mi Házunk, Megálló Csoport, Szomolyai Romákért Egyesület, Igazgyöngy Alapítvány and the Cordelia Foundation.