Media Archaeology Trilogy

(2007-Present)

The only effective form of intervention in this world is to learn its laws of operation and try to undermine or overrun them. One has to give up being a player at the fairground sideshow and become an operator within the technical world where one can work on developing alternatives.

–Siegfried Zielinski, Deep Time of the Media: Toward an Archaeology of Hearing and Seeing by Technical Means (MIT Press, 2006)

Introduction (1919-2007)

Since 2007, I have actively explored the history of certain obsolete audio/visual media technologies, following a very specific line of inquiry:

What sort of desires and fears of their time were these devices designed to address, at what point and for what reason were they discarded, and have their inevitable replacements addressed these concerns any more or less completely?

This has led to a number of media archaeological re-enactments which place these discarded technologies in a contemporary context, coupled with a healthy skepticism of the idea of technological progress.

The three technologies chosen represent distinct moments in the uneasy partnership of utopian cultural-technological aims and dystopian military-technological goals, in the eras previous to, during, and just after the Second World War. These technologies are the optical sound transducer (as found in any sound-on-film movie projector from 1919 up until the advent of digital cinema), the voice-encoder (AKA the vocoder, as found in mid-20th Century telecommunications electronics), and the vector graphics display (as found in most visual computer interfaces from the 1950’s up to the start of the 1980’s).

Part One: TONEWHEELS (2007-14)

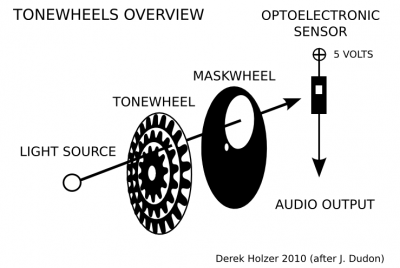

TONEWHEELS is an experiment in converting graphical imagery to sound, inspired by some of the pioneering 20th Century electronic music inventions such as Edwin Emil Welte’s Light-Tone Organ (DE, 1936), Evgeny Murzin’s ANS Synthesizer (USSR, 1937-57), and Daphne Oram’s Oramics system (UK, 1957). Transparent tonewheels with repeating patterns are spun over light-sensitive electronic circuitry to produce audiovisual pulsations and textures, solely using optical overhead projectors as light source, performance interface, and audience display.

Technically, TONEWHEELS uses the same kind of optical sound transducer as any normal movie film projector. In the projector, areas of transparency and shadow on the film encode sound as a modulation of light which falls on a phototransistor, which converts the instantaneous amount of light it sees into an electrical current which can be used to move the membrane of a loudspeaker. In this sound-synthesis system, the linear filmstrip has been replaced with a number of rotating disks, whose speed and design create waveforms of different frequencies and timbres.

The TONEWHEELS performance came to draw heavily on the aesthetics of experimental noise and punk rock music. While delicate tonal sounds can be produced through careful control of the spinning wheel and light source, as the live set progresses it teeters towards the edge of chaos and loss of control.

Ultimately, the project suggests a parallel, alternate evolution where many 20th-Century electronic sound instruments as we know them — such as the inventions of Lev Termen (USSR/USA, 1928) or Robert Moog (USA, 1964), for example — were never developed, and every synthetically produced sound has its origins in the visual domain. A vast amount of historical research went into the project, which can be reviewed at http://umatic.nl/tonewheels_historical.html

TONEWHEELS was conceived during the Art of the Overhead festival (Cologne DE, 2007), supported by residencies at Tesla (Berlin DE, 2007) and STEIM (Amsterdam NL, 2008), and performed live in over a dozen countries.

Part Two: DELILAH TOO (2014-15)

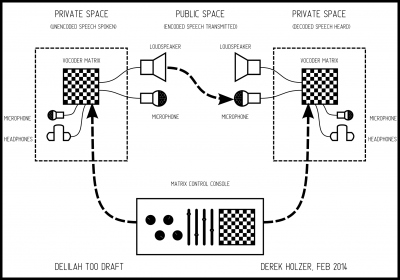

Taking it’s name from the advanced speech security system developed by Alan Turing in the Second World War, DELILAH TOO is based on the voice-scrambling capabilities of the vocoder — a device far better known for its role in the history of electronic music than for it’s cryptographic potential. It took the form of a sound art installation employing voice encryption as a method to protect privacy while still speaking in the public sphere, all the while keeping in mind the personal narratives of Turing (a persecuted British homosexual) and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (an imprisoned Soviet dissident who described his own country’s vocoding experiments in his 1968 novel In the First Circle), each of whom could very much have benefited from the use of this device themselves. In the diagram below, we see two insulated, private cabins in the installation space which transmit and receive encoded speech sonically through the public domain using a “key” generated by a central control system.

A vocoder works by filtering the input signal into a number of frequency bands, measuring the amount of energy present in each band, and transmitting only those measurements along to be resynthesized on the receiving end. This method, the analog ancestor of the digital Fast Fourier Transform, saves in the overall electrical bandwidth needed to carry a voice signal. However, remembering Claude Shannon’s theorem (USA, 1948) that noise is an integral part of any communications system, the encoded voice can also be “scrambled” by transposing the information between the different bands using a matrix. Only if the order of transposition is known, can the signal be unscrambled with an inverse matrix.

In this short demonstration sketch, we first hear an unaltered voice reading Fernando Pessoa’s I’ve gone to bed with every feeling, then the scrambled signal, and finally the descrambled and resynthesized signal.

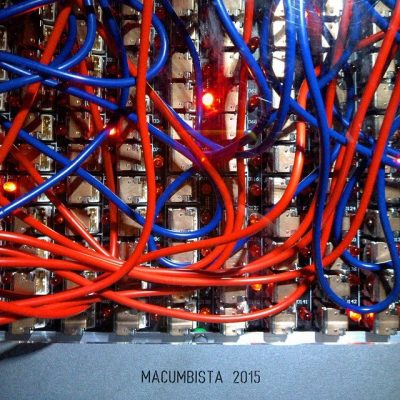

The hardware of DELILAH TOO is constructed from materials common both to mid-20th-Century telecommunications (relays, switches, transmission cables, microphone mouthpieces, and earphones) and to mid-20th-Century sound synthesis (bandpass filters, envelope followers, and voltage controlled amplifiers) as a reminder that each application of voice-encoding technology shares an origin in the military experiments of the Second World War. The algorithms used nowadays by mobile phone networks to compress speech into data packets likewise traces a lineage to this wartime development.

DELILAH TOO was presented as an installation during the CTM Festival (Berlin DE, 2015), and was supported by a working grant from the Foundation of Lower Saxony and a residency at the Edith-Russ-Haus for Media Art (Oldenburg DE, 2014).

Part Three: VECTOR SYNTHESIS (2015-Present)

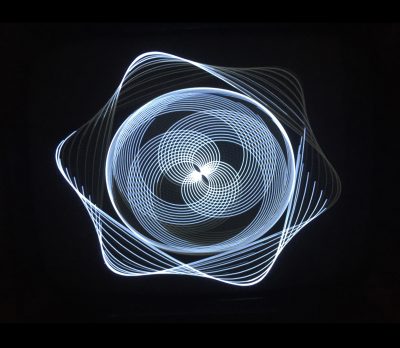

While TONEWHEELS used graphics and light to create sound, VECTOR SYNTHESIS uses audio signals to create light images on an analog vector graphics display. It draws on the historical work of artists such as Mary Ellen Bute, John Whitney, Nam June Paik, Ben Laposky, and Steina & Woody Vasulka among many others. It also investigates the history of the computer as a military calculator dedicated to more efficient ways to drop bombs on other human beings, which was slowly appropriated into the service of artistic expression.

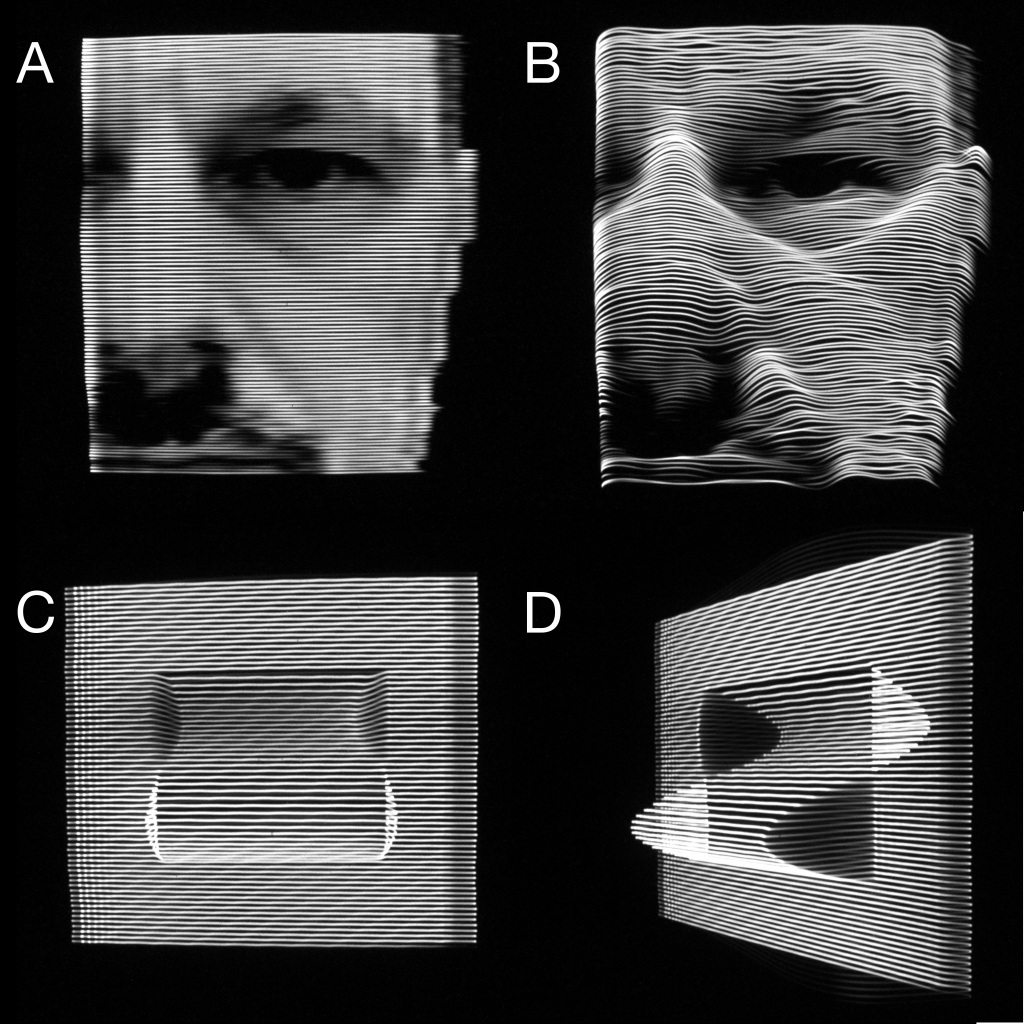

In contrast to conventional video monitors, which rasterize an image into a series of pixels along a succession of scan lines, vector monitors (like their close cousin the oscilloscope) employ the unconstrained vertical and horizontal movement of a single beam of light to trace shapes, points and curves with near-infinite resolution. All of the images and videos in this section were sent as audio signals to a modified Vectrex game console (USA 1982), and photographed from the screen with a digital camera.

Vector monitors represent an early phase of the development of video technology, and were initially used to visualize the calculations of analog computers. As Cathode Ray Tube monitors are rapidly replaced by more efficient flatscreens, the look of the CRT becomes an icon at the same time as the object itself becomes e-waste.

This electronic signal-based technique can generate classic Lissajous figures on the oscilloscope or vector monitor, as well as render geometric shapes and 3D models, or use the mathematics of the signals themselves to create what pioneering video artist Woody Vasulka refers to as “time/energy objects”.

Scan processing refers to a video raster manipulation technique whereby the luma or brightness values of any given area of an image are extracted and employed for further transformations — for example by applying it to create three dimensional depth in an otherwise two dimensional image. This becomes a powerful technique in the language of self-representaion in electronic media.

The culmination of many of these techniques came together during my work with the vintage EMS Synthi 100 (UK, 1971) analog modular synthesizer at the Electronic Studio of Radio Belgrade.

VECTOR SYNTHESIS was largely developed during studies at the Media Lab of Aalto University (Helsinki FI, 2016-19), as well as during residencies at Cirkulacija2 (Ljubljana SI, 2017), the Electronic Studio of Radio Belgrade (Belgrade SRB, 2018), and the Media Arts and Technology department of the University of California (Santa Barbara USA, 2019). The work has been performed live in 14 countries. In October of 2018, I co-organized the Vector Hack conference and festival of experimental vector graphics in Zagreb and Ljubljana in collaboration with Ivan Marušić Klif and Chris King. And in the summer of 2019, I published the book Vector Synthesis: a Media Archeological Investigation into Sound-Modulated Light in a sold-out edition of 700 copies.

Conclusion (2018-2048)

My own personal interest in media archaeology isn’t merely retro-for-retro’s-sake. Rather, it is an exploration of once-current and now discarded technologies linked with specific, imagined utopias and dystopias from other times. The fact that many aspects of our current utopian aspirations (and dystopian anxieties!) remain largely unchanged since the dawn of the electronic era indicates to me that seeking to satisfy them with ideas of new-ness and technological progress alone is quite problematic. Or as Rick Prelinger puts it, “the ideology of originality is arrogant and wasteful.” [On the Virtues of Preexisting Material, 2007/2013] Therefore, an investigation into tried-and-failed methods from the past casts a new kind of light on our current attempts and struggles—and those of the coming decades as well.

–Helsinki, 05 JAN 2018 / 25 DEC 2019